Fresh Food for All - Building a More Inclusive Philly Farmers’ Market

PHILADELPHIA IS UNDOUBTEDLY A MARKET CITY. There are more than 80 seasonal and year-round farmers’ markets in the region—60 within the city limits alone. Echoing national trends including the celebration of local, organic produce and producers, new markets have opened at a steady pace over the last 20 years. According to the Farmers Market Coalition, the number of farmers’ markets in the U.S. has grown from 2,000 in 1994 to more than 8,600 today. With a rich history of community gardening and a vibrant urban agriculture movement, Philadelphia has long understood the connections between healthy food and community. Folks have been selling produce at pop-up street markets here for hundreds of years.

Each week, especially during the summer, Philadelphians load up on the region’s bounty. Yet for all their benefits—fresh food, grower relationships, thriving communal spaces—farmers’ markets are sometimes seen as out-of-touch and elitist. Local and organic produce can be very expensive, placing it out of reach for those with limited budgets. Signals regarding who is welcome are sent by the vendor, product, and programming mix.

As we look toward the next 20 years of farmers’ markets in the city, we set out to identify the elements that can contribute to a more inclusive scene.

ACCESSIBLE AND AFFORDABLE

One basic way to create a more welcoming market is accepting multiple forms of payment. Markets or vendors without electronic benefits transfer (EBT) processing equipment exclude SNAP [Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps] recipients from the mix. Yet the logistics of accepting EBTs can be complicated, from securing terminals to creating a comfortable experience for shoppers.

In Philadelphia, The Food Trust has been working to expand SNAP-enabled markets since 1992, providing infrastructure and resources, including card terminals and promotional materials to make shoppers aware of their options. This was born of a simple insight from founder Duane Perry: Folks citywide were coming to shop at Reading Terminal for the quality produce and affordable prices, thanks in part to the fact RTM has long made shopping comfortable and easy for SNAP recipients. Why not bring a similar experience to the neighborhoods via farmers’ markets? The Food Trust has since grown into a nationally recognized nonprofit.

As SNAP acceptance has expanded at farmers’ markets, so too has creative thinking about how to make local fruits and vegetables more accessible for everyone regardless of income.

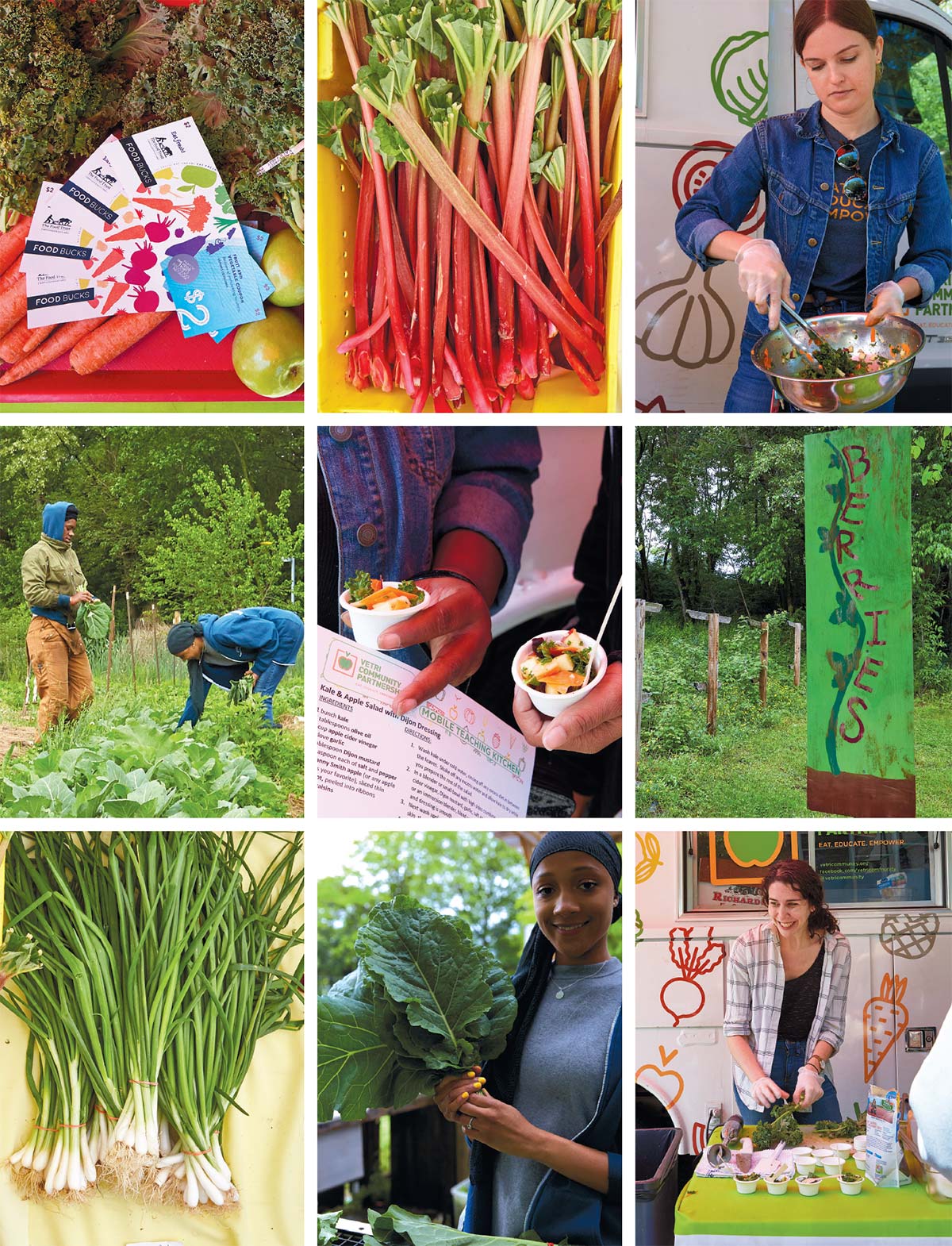

When the Philadelphia Department of Public Health and The Food Trust launched Philly Food Bucks in 2010, Meghan Filoromo was a SNAP recipient living near Clark Park Farmers’ Market, the city’s oldest yearround producers-only market. The premise of the program was simple: For every $5 of SNAP benefits spent at participating markets, customers received $2 in Philly Food Bucks, redeemable at any of the organization’s farmers’ markets.

It made an immediate difference, Filoromo says, putting healthy produce in her reach. It was something valued. As a Temple University student, she helped launch the campus farmers’ market. She also apprenticed with Landisdale Farm, working in the field and at Clark Park, where they have been a longtime vendor. Yet as a young professional, the foods she believed in were difficult to afford.

“I was on SNAP and I was, like, ‘This is so cool, this is really great,’” she says. Today, Filoromo extends that experience to others as manager of The Food Trust’s Farmers’ Market Program. “Having personally benefitted from receiving Food Bucks, I believe in it so strongly.”

That’s a big deal in a gentrifying city, says Clark Park Farmers’ Market manager Lauren Faux, who came on at Clark Park in February after managing the markets at Overbrook, 58th and Chester and in the city of Chester.

“Accepting ACCESS cards and giving out Food Bucks, offering benefits and perks to help people stretch their money—that is a way to bring in the community people who have lived here forever, or who might not be as rich as the other people who are moving here and displacing them.” Tellingly, she says, prices vary widely depending on location. “If you’re going to put a farmers’ market somewhere you have to be aware of who you are trying to attract. Can the people who live right there afford your stuff?”

In 2017, the most recent year for which data is available, $874,536 in Philly Food Bucks were distributed; The Food Trust reports a 300 percent spike in SNAP payments. That’s a 300 percent spike in SNAP payments from its launch in 2010.

Inspired by those numbers, the organization is establishing community advisory boards to guide their markets into the future. It’s hiring more neighborhood-based market managers. It is also extending distribution partnerships with everyone from block captains to the Philadelphia Housing Authority and adding places where Food Bucks can be spent, including partner markets, grocers, and farm stands.

Vetri Community Partnership travels to Clark Park Farmers' Market to teach healthy cooking basics.

Vetri Community Partnership travels to Clark Park Farmers' Market to teach healthy cooking basics.

Offering benefits and perks to help people stretch their money—that is a way to bring in the community people who have lived here forever.

HEALTH-AND EDUCATION-FOCUSED

Riding on Food Bucks’ success, sibling program Philly Food Bucks Rx seeks to reach people in their doctor’s office, where they may discuss nutrition and food-access challenges, topics that can feel stigmatizing. Similar to the Fresh Rx program at St. Christopher’s Hospital, which provides produce boxes by prescription, Food Bucks Rx expands buying power at farmers’ markets, corner stores, and supermarkets.

According to Julia Koprack, senior associate for The Food Trust, more doctors, dieticians, and nurse practitioners are talking with patients about food insecurity during big-picture health conversations. While specifics are customized to each partner practice, the goal is to provide roughly $30 per person a month.

“It’s a way to directly respond to issues around food insecurity. It’s a way to help with preventive medicine when we see so much chronic disease,” Koprack says. “When we talk to shoppers in Phil- adelphia across the board, whether it’s at a grocery store, supermarket, or farmers’ market, a key theme that we hear over and over again is that price matters.” It’s clear from these conversations that most people would feed their families healthier food if only they could afford it.

Another tool that promotes food as medicine is education.

Anyone who has spied the Vetri Community Partnership’s mobile kitchen, bedecked with leeks, strawberries, and other fresh produce, can see that healthy ideas are always on the menu there. At Clark Park Farmers’ Market, the kitchen sets up on spring Saturdays, distributing Food Bucks during demos. (The Food Trust’s culinary education team takes over for the rest of the season.) One recent weekend, Vetri Cooking Lab educator Tamyah Brice enticed shoppers with a vegan twist on potato salad from Leanne Brown’s cookbook Good and Cheap, olive oil standing in for the dairy.

“You see a lot of health issues, especially in the Philly area,” says Brice, who majored in public health at Temple. “It’s super important to emphasize healthy living and healthy lifestyles—not even saying, per se, eliminating all of the bad foods, but incorporating the good foods.”

That’s an important, if subtle, point. Take that potato salad. As Brice prepped the dish, one shopper suggested using curry and oregano rather than the suggested Dijon and lime. Others were firmly pro mayo, or even basil vinegar. Not everyone is going to have a recipe’s ingredients, Brice says, whether due to preference or budget. “So, what are some of the things that you can substitute? What are some alternatives?”

Engaging shoppers with live cooking demos is one way to teach them about healthier eating, but education can also be baked into market operations.

Henry Got Crops Farm Market in Roxborough is run by Weaver’s Way in partnership with the W.B. Saul High School, Philly Parks and Rec, and Food Moxie. Located on the grounds of the school—one of only a handful of remaining agricultural high schools nationwide—it farms on site and employs student interns at the market.

“They work all through the summer into the fall,” says market manager Lauren

Todd, who recalls how empowering her early job experiences were and enjoys guiding the students’ journey.

At the market, students talk to customers about food and agriculture. High school students and faculty also receive a 15 percent market discount.

Todd’s hope is that students learn to think critically about the power of local food systems. When neighbors grow food for each other, she says, they build a safety net. “After last season, which was terrible for local farmers, it made all of us on the farm team realize how fortunate we are to have that co-op community. Fortifying community gardens and urban farms is going to be more and more important to building our resiliency.”

Sankofa Community Farm focuses on education, teaching neighborhood kids how to farm.

COMMUNITY-CENTERED

If creating accessible, health-focused markets is a first step toward inclusivity, promoting markets that rise from and serve their neighborhoods is the key to lasting impact.

Early in the season at Sankofa Community Farm in Bartram’s Garden, the four-acre expanse was seemingly fallow. Yet beneath the soil, roots from last year’s plants were at work, feeding a rich microbiotic community. Observing the field during a busy volunteer day, paid intern and high school senior Sybria Deveaux, who manages Sankofa’s on-site farm stand, reflected on the farm’s importance to her neighborhood. “I had never grown food before, but I’m assuming if I did, I probably would have thought it was just growing food,” she says. “Doing this work matters because it affects someone.”

Initially part of the University of Pennsylvania’s Agatston Urban Nutrition Initiative, the youth-powered space became independent and rebranded in 2017, with continued support from from Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, Bartram’s Garden, and the city. Sankofa, in the Twi language of the African country Ghana, evokes the reclamation of things left behind. Focused on youth education, the project has evolved from an initial focus on food access to emphasize three themes: being spiritually rooted, intergenerationally connected, and African Diaspora centered.

Each summer, two dozen students spend six weeks rotating through positions, from field to market. There are also 14 paid, year-round internships. Through the experience, youth learn about the African roots of natural agricultural practices deemed “trendy,” from permaculture to crop rotation. In the farm’s diasporic garden, planted with bottle gourd, sorghum, and African rice, they trace the paths of the food and people of the Diaspora, covering African civilizations, the Middle Passage, and the American South.

The goal is to reframe students’ relationship to the land, to food, and to their histories, imparting the skills and perspectives that underlie sovereignty. Deveaux says it has been transformative. “It is kind of unbelievable. I’m really here, doing the work of my ancestors, but not in the same sense. Definitely still catering to the land, because no matter what happened in the past, the land didn’t oppress us.”

Lessons in hand, students make neighborhood connections at the farm’s Thursday market, gathering over tables piled with cooking greens, carrots, and sweet potato leaves—the latter introduced on the recommendation of a student’s father, who explained their importance to Philadelphia’s Liberian community. “I really like the market, and the idea of selling what we grow to my community members,” Deveaux says. “You’re giving people nutrients that you really worked hard to make.”

Ty Holmberg, who co-directs Sankofa with Chris Bolden-Newsome, says that’s a powerful exchange, rooted in hyperlocal needs and values. “How do we authentically partner and get guided by the intergenerational community that’s out there in Southwest Philly?” he asks. In part, as the farm demonstrates, the answer is by growing its next generation of leaders.

Deveaux frames her answer to that question as a story. “That’s Mr. Bill from down the block. He’s very cool. He has a farm, and I love his food. I buy apples off of him,” she begins. “Then you have kids, and now your kids know Mr. Bill, too. That is what a really good farmers’ market can look like—where people are all from the same community, or from around that community, and are trying to bring healthy food and eating back.”

ENVISIONING PHILLY'S FUTURE FARMERS MARKETS

When discussing how to build a more inclusive farmers’ market scene, several themes echoed through our conversations.

FRESH

“You get fresh food from local farmers, and they’re not brought from other states or countries.” —Brenda Houston, Clark Park Farmers’ Market shopper

WELCOMING

“If you’re going to devote yourself to providing nutritious food, you’ve got to look at every way you can to reach as many people as you can.” —David Hodges, Collingswood (NJ) Farmers’ Market director

EMPOWERING

“I don’t want to have this future where everything is owned by Wal-Mart and Nestle Co. Little farmers’ markets feel like a resistance.” – Lauren Faux, Clark Park Farmers’ Market manager

ACCESSIBLE

“There are a lot of issues here that need to be addressed around income inequality, gentrification, development, and access to land.” —Meghan Filoromo, Clark Park Farmers’ Market shopper

SUPPORTED

“Food Bucks have been a key part of being able to grow. Investment from the public and private sector can really be key.” —Julia Koprack, senior associate, The Food Trust

ROOTED

“We need to do better in hiring people from the communities. Also prioritizing farmers of color.” —Ty Holmberg, co-director, Sankofa Community Farm