Farming in Climate Chaos

IF YOU TALKED WITH ANY FARMER DURING THE 2018 GROWING SEASON, YOU HEARD ABOUT THE RAIN.

In the spring, growers reported a slow, wet start; by mid-summer, many looked weary on rainy market days; by fall, stock at their stalls was scant—squash, carrots, cabbages, and potatoes all absent. Through the entire growing season, farmers lamented the rain just wouldn’t let up.

“The 2018 farm season will be burned into our psyches forever as the most devastating year on record for our farm.” That’s the first line of Blooming Glen Farm’s season wrap-up, posted on the farm blog by owners Tom Murtha and Tricia Borneman.

Last year, Village Acres Farm and Foodshed north of Harrisburg recorded 15 inches of rain in just three days. Harrisburg logged 16 record-high days of rainfall throughout the year. Three Springs Fruit Farm in Adams County accumulated 18 percent of their expected annual rainfall in four days. In September, the Philadelphia area got pounded with nearly five inches of rain in 24 hours.

The heat hurt, too. South Jersey sweltered through the warmest August (tied with 2016), the second-warmest October, and the third-warmest September ever recorded. Barry Savoie at Savoie Organic Farm in South Jersey lost count of days above 90 degrees. The last five years have been the hottest on record.

“What we’re finding is that climate change boils down to two conditions: hotter and wetter,” says Rachel Valletta, an environmental scientist and director of the Climate and Urban Systems Partnership, a Philadelphia-based network of climate educators. If the predicted mid-range emission scenario (a situation in which moderate but not really adequate reductions in fossil fuel use are made worldwide) comes to pass, scientists are expecting three weeks of degree days above 90 by mid-century and more frequent and heavy downpours every summer.

“Scientists are seeing a reorganization of how precipitation forms in the atmosphere,” Valletta says. “As temperatures increase, more moisture is evaporating from the soil; as air masses warm, they can hold more moisture.” Which means the subsequent rainfall comes in buckets, not showers. According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment report, the amount of annual precipitation recorded in our region that falls in the form of heavy rain events has already increased by 38 percent from 1901 to 2016.

Last year’s heavy rains and heat caused a host of challenges for farmers. Muddy fields forced planting schedules to be pushed back; newly planted seedlings drowned in floods; root crops that sprouted leafy green tops rotted under the surface of the waterlogged earth. The relentless heat stressed plants, destroyed fall crops, and, combined with the humidity, caused weed, disease, and pest pressures to surge.

Though farmers in our region have been dealing with challenges caused by climate change for decades, the 2018 season was jarring. Huge crop losses spurred action. Last year’s weather conditions caused farmers to realize they have to adapt faster if they want to keep growing food for a living.

This season, farmers in our region are scaling back their ambitions and business plans to mitigate risk, growing more crops in high tunnels where the weather can’t destroy them, and doubling down on soil health, the heart of sustainable agriculture. It’s taking persistence and innovation for these farmers to stay resilient in the face of climate chaos. But if anyone’s up to a job that daunting, it’s farmers.

“FROM ABOUT 300 PLANTS IN A TUNNEL, I GET MORE TOMATOES THAN I DO FROM 2,000 PLANTS OUTSIDE.”

SOIL HEALTH

The health of a farmer’s soil determines not only the health of their crops, but also how well the fields can tolerate heat and rain and effectively sequester carbon. Improving soil health is the foundation of both sustainable and regenerative agriculture. It’s what Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture (PASA) director and farmer Hannah Smith-Brubaker is focused on at the organization and on her farm. “Because we’re always asking so much from the soil, we’re always thinking about paying it back,” she says.

Her family raises produce, lambs, and poultry on their farm, Village Acres Farm and Foodshed, in Juniata County. Their rotational grazing system is key to maintaining resilient fields. After fall harvest, they plant cover crops, which help to prevent erosion, suppress weeds, and fix carbon in the atmosphere and nitrogen in the soil. When they decompose in the spring, they’re fuel for microorganisms like fungi, bacteria, and invertebrates that provide nutrients for the next season’s crops.

The following fall, Smith-Brubaker sows winter grain like triticale (a cross between wheat and rye), which is harvested the next summer. For the two to three years, that same field is used to grow hay for winter feed and as pasture for the sheep and chickens. The animals mow down grasses, eat seeds and bugs, and spread nutrient-dense manure over the field. Perennial grasses that take over the field not only feed the animals, they also hold the topsoil in place and can suck up excess water.

This rotation, and a minimum three-year break from nutrient- draining vegetable production, gives the ground a chance to rest and regenerate, Smith-Brubaker says.

Last fall, Village Acres recorded 15 inches of rain on the farm in three days. This season, they decided to convert a third of their vegetable field to permanent pasture, where their hens and sheep will graze on perennial plants and deep-rooted grasses. “That is our best hope for absorbing water,” Smith-Brubaker says.

They’re also expanding their multifunctional buffer of forest edibles like paw paws, and ramping up perennial crops like asparagus and rhubarb, which require minimal soil disturbance—the plants come up year after year without the need for tilling.

Tilling breaks up soil aggregates, tiny masses of particles held together by clay and organic matter like roots and fungal hyphae. The more intact these clumps are, the more water the soil can take up and release slowly as needed.

“One of the ironies about how climate change is playing out in our region is that we’re getting heavy rainfall, concentrated in short deluges with droughts in between,” says Franklin Egan, director of education at PASA. “Farmers need to figure out how to manage too much and too little water at different times throughout the season.”

Egan coordinates PASA’s Soil Health Benchmark Study, which helps farmers measure the health of their soil and discuss improvement strategies with their peers. The farmer-led research project is funded by the National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) and grew from 12 grower participants in 2016 to 59 this year.

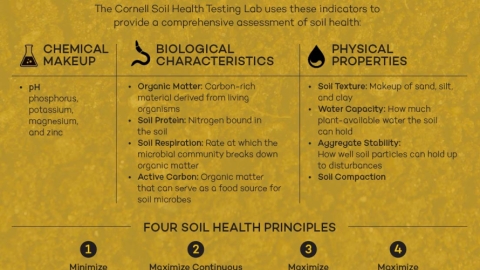

Growers send samples to Cornell University’s Soil Health lab, which measures chemical, biological, and physical soil attributes and determines scores in each category based on the soil type. PASA collects information from each farm about their growing methods, specifically tillage, crop rotations, and use of soil amendments like minerals and compost. The final benchmark report shows how their results compare to peer farms and offers specific resources for continued soil improvement.

BY PAUL PRESCOTT-ADOBESTOCK.COM

BY PAUL PRESCOTT-ADOBESTOCK.COM

SCALING SMART

Tom Murtha and Tricia Borneman have been growing vegetables and flowers organically on 30 acres in Perkasie for 13 years. From their very first season, they’ve practiced sustainable farming methods like composting, cover cropping, and crop rotation in order to build soil health and prevent erosion. “There’s a deep sense of stewardship that goes along with this life,” says Murtha.

He and Borneman were devastated last year when, despite all the work they’d put into taking care of their land, fields still flooded. Seeds washed away or failed to germinate in waterlogged soil; they weren’t able to transplant starts from the greenhouse into the soil at the right times; and they lost 80 percent of their fall crops—cabbage, kale, potatoes, carrots, Brussels sprouts, beets, and rutabaga rotted in the field.

All in all, Blooming Glen Farm lost about a third of their anticipated income last season.

The financial stress prompted Murtha and Borneman to take a hard look at the business and revisit their goals for the farm. “We asked ourselves, ‘Why are we doing this? Is this scale too big for us? If we have another season like this one, can we handle it?’” Borneman says. Answering these questions prompted the couple to scale back for 2019.

They’re participating in two farmers’ markets this season, down from three last year, and selling to fewer wholesale outlets. “We’re focusing on not spreading ourselves too thin,” says Borneman. Their partnership with Poppy’s Greengrocer, a new community market expected to open in June in New Hope, will enable them to spend less time and resources on marketing and outreach.

Borneman and Murtha had to make strategic decisions about labor this season, too. They couldn’t afford to pay a salary for an assistant farm manager like they did last year, and they’re making do with about half the workers they usually hire in the shoulder seasons. They’ll get by relying on local high school students and seasonal workers for part-time help in peak season.

“When you have short periods of good weather you have to act fast,” Borneman says.

DIVERSIFY AND COVER

At Savoie Organic Farm in Williamstown, New Jersey, wide stripes of silvery white stretch out over the field alongside rows of green. Under heavy plastic secured over metal frames—high tunnels—tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants are protected from heavy rains.

“If you don’t have a high tunnel, then you’re really at the weather’s mercy,” says Barry Savoie, who runs the farm with his wife, Carol. Since 2012, they’ve invested in five high tunnels, which cost about $7,000 each. The structures are about eight feet tall, 20 feet wide, and 100 feet long, with plastic walls that can be rolled up or down with a hand crank to adjust temperature and airflow.

The Savoies purchased two new high tunnels last fall as insurance against increasingly wet seasons. They protect high-dollar and moisture-sensitive produce like tomatoes. “Th ink of it as an umbrella over your crops,” Savoie says.

Outside, tomatoes are more susceptible to disease like bacterial leaf spot, which can spread by wind-driven rain and infect plants with consistently wet foliage. “What happens in a hot, wet environment is fungus and bacteria go nuts,” Savoie says. Inside the high tunnel, he can regulate moisture, using irrigation to deliver water directly to the soil at the base of the plants as needed.

And the plants reward him with higher yields. “From about 300 plants in a tunnel, I get more tomatoes than I do from 2,000 plants outside.” Plus, the fruit—free of mold spots and cracks caused by plants sucking up too much water—sells better at market and stays good longer.

As of result of their tunnels, last season, the Savoies weren’t devastated by the storms that slammed farms across the state (2018 was the wettest year on record in New Jersey). Though they’ve dealt with intense rain in recent seasons, their biggest challenge last year was heat. The couple is used to sweltering summer months, they say. “But that 90-degree weather stayed with us until the 15th of October.”

The heat wrecked their fall crops including lettuces, radishes, broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower. “We had 80 percent mortality in the first two days of planting our cabbages and cauliflower,” Savoie says. Under prolonged heat stress, plants’ ability to photosynthesize is inhibited, and in turn, their ability to produce fruit.

But the Savoies don’t have their eggs in one basket; they grow about 70 vegetables and as many as 10 different varieties of each. One variety might be more heat-tolerant, another moisture- loving, which means they’ll have a good harvest of something no matter what the weather brings. It’s a practice they’ll lean into even more heavily in the years ahead.

ON THE FRONT LINES

As folks who work outside every single day for more than eight months of the year and rely on sun and rain and soil to make a living, farmers are the most in-touch with our changing climate. And the best solutions come from those who are most impacted.

“Farmers are uniquely positioned to implement solutions that could mitigate climate change,” says Smith-Brubaker.

Healthy soils sequester carbon at a faster rate and store it longer than soils that have been over-tilled or over-extracted. Growing more crops like tomatoes under cover reduces the need for chemical fertilizers that are detrimental our food- and watersheds. Cultivating an ecosystem rich in biodiversity ensures a more adaptive natural environment.

These stewards of the land are adapting not only for their own farms’ survival, but for our survival, too.

WHO'S GOING TO PAY?

For the past decade, local farmers have been dealing with extreme weather that makes it more expensive to grow food, but most haven’t raised their prices. The growers I talked to for this story said they thought they would lose customers if they charged more.

The reality is, farming is getting harder, riskier, and more expensive, and all of our lives depend on fi guring out ways to grow food despite dramatic weather. The cost of this process – investment in infrastructure, increased labor required, huge losses incurred – shouldn’t be the sole responsibility of the farmer. So, if you do notice a bump in prices this year, remember that it’s important we all contribute to the solutions.