Foraging for Mushrooms in a Day's Work at Mainly Mushrooms

I still remember the mushrooms my Uncle Pasquale would bring to my mother’s kitchen after his hunting trips in the nearby woods. None of the mushrooms my mother usually prepared were as tasty—or strange-looking—as the ones my uncle brought her. Years later, I found out why. He not only hunted for rabbit and deer, but was also an avid wild mushroom hunter, or forager.

Food memories are some of our most vivid, keeping us connected to family, traditions and friends. I was reminded of this when I visited Chris Darrah at his home for dinner to talk about wild mushrooms. Darrah, who grew up in Bucks County, forages for wild mushrooms and sells them under the name Mainly Mushrooms at farmers’ markets and to chefs.

Darrah’s memories of edible fungi are some of his oldest. When he was just 8 years old, one of his favorite foods was the huge puffball mushrooms a friend’s dad foraged and cooked for them. “He’d fry them up for us like pancakes, sprinkle them with salt and pepper and pour maple syrup over them. They were better than the real ones,” says Darrah.

Another pivotal time, many years later, was when he tasted his first wild morel, given to him by a foraging friend who would eventually become his mushroom mentor. “It tasted like the forest after it had rained—very intense, fresh and earthy.” He knew then that he wanted to learn to forage on his own.

Outside, it’s early January, but Darrah’s already thinking of spring. Keeping him warm are thoughts of walking into the woods, easing down onto the soft and wet dirt and walking out triumphantly with mounds of morels, their gumdrop shape and honeycomb caps rich with wild flavor.

“That’s the best time to look for mushrooms, after it rains.” He’s talking to me, but also to his wife, Patty, who’s heard this excuse before for his perpetually muddy clothes. He needn’t worry. She loves the taste of wild mushrooms as much as he does and extra laundry is a small price to pay for them. Then she darts into the kitchen to tend to tonight’s dinner—a mushroom feast.

SEEK AND SAVOR

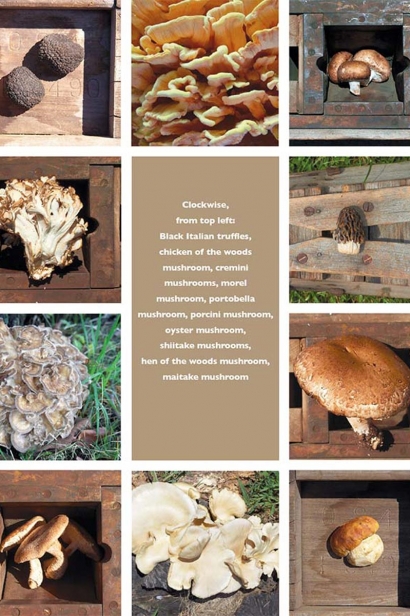

Morels mark the beginning of the mushroom seasons, says Darrah. They’re followed by chanterelles, black trumpets and chicken-ofthe- woods in summer. Maitake (also called hen-of-the-woods), hedgehog, cauliflower and lion’s mane mushrooms turn up in fall. Oyster mushrooms are scattered through the seasons into winter.

Each kind has its own distinct flavor, from the intense earthiness and nuttiness of the morel to the chanterelle’s floral notes, and from the meaty flavor and texture of a maitake or a black trumpet to the milder taste of ones like chicken-of-the-woods (which, when cooked, taste something like their namesake).

Unlike cultivated white button mushrooms, wild mushrooms should never be eaten raw. Cooking releases their flavor and tenderizes them, making them easier to digest. Mushrooms are high in minerals that boost the immune system and fight against infections and cancers as well as arthritis and lupus—ratcheting them up among the top foods to eat for good health.

Still, it’s their earthy flavor that inspires chefs and home cooks alike to celebrate their fleeting seasons.

“Chanterelles,” says Darrah, “are great in omelets or sautéed and used as a topping for chicken breast, and are excellent roasted with onions, apples and butternut squash.” Grill oyster mushrooms with a sprinkling of za’atar for an exotic flair, he says, or use in a stir-fry. “Maitake are wonderful sautéed in olive oil with shallots and sundried tomatoes for bruschetta.” A good way to test out a mushroom’s flavor profile, he says, is to sauté them first in butter or a mix of olive oil and butter. “But butter definitely for morels,” he says, “Morels deserve butter.”

Never wash or rinse wild mushrooms, says Darrah, just give them a shake to ferret out any bugs or brush them with a damp paper towel or dry mushroom brush. Stored loosely in a paper bag in the fridge, they’ll keep up to a week.

Just as each mushroom offers a different flavor profile, so do they vary in their favorite hiding spots. Look for morels around orchards, especially old apple orchards. Others like maitake favor the base of oak trees and stumps; chicken-of-the-woods lodge on tree logs; and black trumpet, perhaps one of the hardest to spot because it looks like dried leaves, prefers the beech tree as well as the oak. But don’t only look to the ground. Chicken and oyster mushrooms grow on tree trunks, their fan-like petals clinging like shelves.

TOOLS OF THE TREK

To harvest the mushrooms, Darrah prefers a folding knife with a hawksbill blade. All mushrooms should be cut free (not pulled from the ground) to keep the underground fungus from damage. “Think of the mushroom as a flower,” he says. “Bring a mesh bag or milk crate, something with holes to allow the spores to drop as you forage [like seeds, spores are the beginnings of new mushrooms]—and keep dry clothes in your car.” Other essentials for a foraging expedition? Bug repellent, waterproof boots, a rain poncho or pullover, a good field guide to East Coast mid-Atlantic mushrooms, a frozen water bottle and a compass. Your GPS won’t help you here.

Darrah also advises learning to make spore prints and microscopic slides of the spores. The prints are made by removing the mushroom’s stem and placing the cap gills-down on paper for 24 hours. At the same time, slip a slide under a cap to catch spores. (A good way of learning how to do both, he says, is with a reliable mushroom field guidebook.) The spore print will identify the color of the spores and the slides, when placed under a microscope, will identify the spore’s shape and size.

Both steps are crucial in helping detect false or poisonous mushrooms. Most edible mushrooms have look-alikes that can be deadly. “There’s no room for risk. If I’m not 100% positive, I won’t eat or sell it,” says Darrah. Before you even consider snipping your first wild mushroom, go out with experienced foragers, join a mycological group and go on mushroom forays.

Along with the ones he forages, Darrah sells mushrooms from a network of foragers across the country and in Europe, enabling him to extend the mushroom seasons for his customers. For example, he says, morels have a very short growing season, lasting only a few weeks when conditions are right (wet from recent rain and good humidity).

Along with wild mushrooms, Darrah sells cultivated ones, such as portobello, shiitake, maitake, oyster, and cremini; dried morels and black trumpets; dried porcini imported from Italy; and domestic and imported truffles.

FOREST TO TABLE

As we enjoy a glass of wine with cheese (a young Parmigiano-Reggiano, an aged Manchego and a creamy gorgonzola) before dinner, he shaves ribbon-thin slices of a Pacific Northwest white truffle onto a dish.

“Try this on your next piece of cheese and taste the difference,” says Darrah. The fullness of the truffle’s earthy flavor doesn’t hit me full force like its Italian cousins from Alba would. Instead it sneaks up on me gradually, bringing out the nuttiness of the cheese and draping it in a soft note of garlic.

Unlike wild mushrooms, truffles need no cooking. They can be shaved and eaten raw, he says, or served on top of a dish such as a risotto or scrambled eggs. The heat from the food will bring out even more of the truffle’s nuances.

When Darrah first started selling at the Doylestown Farmers’ Market, customers, unfamiliar with wild mushrooms, were hesitant to buy and prepare them. That’s when he turned to his wife, an enthusiastic cook. On market days Patty started bringing copies of recipes to match his mushrooms. It wasn’t long after that Darrah and his wild mushrooms became a favorite at the market, prompting him to expand his business.

Darrah now sells at farmers’ markets in Doylestown, Wrightstown, Ottsville, Lansdale, Saucon Valley and Frenchtown, New Jersey, and to a growing circle of chefs who use his mushrooms. One of his fi rst was Marlene Zakes of Zakes Cafe in Fort Washington. “Wild mushroom salads have become a classic of ours,” she says. Zakes pairs the mushrooms with seasonal fruit, nuts and cheeses, such as sautéed morels with a farmhouse cheddar, local apples and candied walnuts for spring, and, in summer, chanterelles, local berries and toasted almonds. Ed Batejan of Peachtree & Ward and Pomme, both in Radnor, is known for his chicken served with handmade wheat orzo, morels and sautéed spinach, dressed with a chicken consommé. He likes to be inspired by what mushrooms are in season, such as yellow chanterelles, bluefoot (also called blewits) and cinnamon cap mushrooms. “I’ll call Chris up and ask what he has,” he says.

Over at Sprig & Vine, a vegetarian restaurant in New Hope, chef and owner Ross Olchvary uses mushrooms much like seafood or meat. “They’re ideal as a centerpiece of a dish or as a fl avor focal point,” he says. It’s not unusual to fi nd more than one variety of mushroom featured on his menu, though wild maitakes are his favorite. “There’s a meatier fl avor to them,” he says, “but that aside, it’s really their texture and larger size that sets them apart, making them great to grill or roast without falling apart.”

It’s hard not to be captivated by the taste of wild mushrooms—no matter the cooking style. When I fi rst met Darrah years ago at the Doylestown Farmers’ Market, I was too late for morel season, but he had lovely golden chanterelles. So seductive was their appearance, coupled with Darrah’s knowledge and charm, I couldn’t resist and brought some home to enjoy.

Sitting now at the Darrahs’ table before Patty’s array of wild mushroom dishes, I’m reminded of the ancient Romans who so prized mushrooms that it’s said that a guest could gauge his worth by the number of different mushrooms he was served. I counted seven. The mushrooms made me feel like an honored guest—and one leaving with another mushroom memory.