Perennial Pursuits

A South Jersey-based network of grassroots gardeners fights climate change

Headquartered on an unassuming patch of farmland in Salem County, the Experimental Farm Network is trying to save the world from climate change.

On three acres of land and a few square feet of space in a small greenhouse, Nate Kleinman and Dusty Hinz manage a menagerie of rare, intriguing and delicious plants. In their view, an approach to agriculture that’s based on diverse perennial plants with unique properties is the first step on the path to mitigating—and maybe even reversing—climate change.

The tools in their arsenal? Rare seeds, cuttings, tubers and other germplasm (living plant genetic material), some decades old, sourced from all over the world through outlets ranging from the USDA to neighboring farmers to friends and fellow seed savers across the country. Not to mention a group of 200 or so eager amateur growers and professional researchers from as far away as Norway, South Africa, Alaska and Guam, all of them eager to grow these unusual plants in their own backyards.

For a dedicated urban gardener and produce enthusiast like me, visiting the EFN’s headquarters is a bit like visiting Willy Wonka’s factory, if Willy Wonka were really into sorghum.

Kleinman and Hinz walk me through the small greenhouse space, rattling off acquisition stories, Latin names and fun facts about the plethora of rare varietals the organization has propagated. Guanabana makes a delicious tropical fruit and its leaves can be used for cancer medicine. Here’s jojoba, a drought-tolerant tropical plant that produces a seed that can be pressed for oil that’s useful not only for cosmetics, but also as a potential petroleum replacement. An Iranian variety of sainfoin, a relative of alfalfa, provides forage for ruminants, reducing the amount of methane they expel even when it’s just 5 or 10 percent of their diet. Here’s a chickpea variety that pops like popcorn. This extra-long variety of pine nut is a delicacy in Tibet. Several trays of seedlings are marked “Homs” in black Sharpie; they’re pepper, eggplant and squash varieties that the USDA acquired in the late 1940s from the now war-torn Syrian city.

Hinz and Kleinman met several years ago during Occupy Philly; both had been working in urban farming in and around the city. Along with a background in grassroots political organizing, Kleinman already had thousands of intriguing seeds in his collection after years of amateur research and acquisition. After the two connected at Dilworth Plaza, Hinz says, “We had our sights set on trying ag in a larger scale to start trialing all these different seeds that Nate had acquired through the years.”

The stated mission of the Experimental Farm Network is to “fight global climate change and ensure food security far into the future by facilitating collaboration on plant breeding and other agricultural research”—which sounds like a tall order for two green-thumbed guys in South Jersey.

It is—and that’s where the network comes in.

While its current epicenter is the Elmer home base, the network allows Kleinman and Hinz to run crop trials all over the world. They can send seeds to climates that are more hospitable to certain crops: Chilgoza pine nuts, which originate in the Himalayas, might not do well in South Jersey, but a network member in Colorado provides a great climate for this crop.

Introducing varietals to new climates is only a small part of the picture, though.

While nonprofit organizations, government programs, university researchers and pioneering individuals have dedicated themselves to preserving biodiversity and discovering the potential of plants, Kleinman and Hinz hope to foster collaboration between these silos of activity, focusing on goals like breeding viable perennial grains and oilseeds that can have large-scale agricultural applications and can mitigate climate change. Such plantings can potentially remove a significant amount of carbon from the atmosphere.

“These things are within reach, but they’re going to take a lot of work, and it’s going to [take] a long time,” Kleinman says—and he’s talking decades, not years. “There needs to be a serious, even multigenerational effort to make these things a reality.”

“It’s kind of upsetting even hearing the supposed ‘progressive’ Democrats talk about climate change,” Hinz says. “They’re just talking about renewable energy. And that’s important, but to leave agriculture out of the equation is doing a disservice to everyone, because we really could be sequestering significant amounts of carbon just by focusing on perennials [and] doing rotational grazing systems with animals.”

We’ve all heard about the positives of organic agriculture—and there are plenty of clear reasons to keep substances that are harmful to humans and wildlife off our food and out of agricultural and wild ecosystems. Promoting biodiversity by growing rare or old plant varieties makes sense, too. But what’s so special about perennials? How can plants that survive year after year help us not just adapt to the changing climate but also mitigate it?

A big question like this requires a multi-pronged answer. “Perennials are useful for climate-change mitigation because you don’t need to till the soil if you have a perennial field—you don’t need to waste energy replanting all the time,” Kleinman says. The reduction in fossil-fuel use that results when a farmer doesn’t need to till her fields on a gas-powered tractor to raise productive crops is significant: “Our agricultural system contributes almost as much to climate change in carbon emissions as transportation does, maybe more.”

And perennials provide even more benefits: By nature, Kleinman says, perennials grow more efficiently than annuals, and their huge root systems prevent erosion, build healthy soils and help the plants sequester carbon from the air in the soil. Crops like sorghum can draw carbon from the atmosphere while providing the raw material for everything from sweeteners to bread to beer.

Growing rare or forgotten seeds can help farmers, gardeners and eaters adapt to a climate that’s already changing. “We’re not just worried about fighting climate change—we’re worried about surviving it,” Kleinman says. “With the climate changing so fast, the crops that people can grow in any given area are going to change. We have no idea what’s going to be viable or important in 20 years or 50 years or 100 years.”

By nature, part of the EFN’s mission involves growing and promoting plants native to South Jersey and the mid-Atlantic. They’ve planted blight-resistant Chinquapin chestnuts, along with Dietrich’s wild broccoli raab, a wild turnip found right on the farm property and named for the EFN’s landlords. Several varieties of Campbell’s specially bred tomatoes, pawpaws and Nanticoke squash, one of their favorite crops, are also on their list of native favorites.

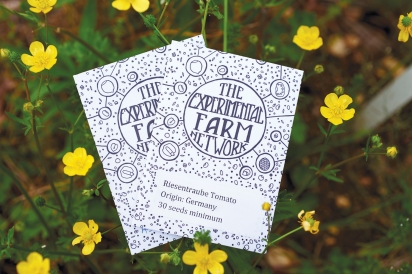

Hinz and Kleinman are excited to connect with local growers, too. One is Joe Kieffer, owner of Triple Oaks Nursery in neighboring Franklinville. Kieffer connected with the EFN through the Library Seed Bank in early 2016. Triple Oaks sells EFN seed packets; customer favorites include the wild raab, tomatoes and a particular variety of okra that’s a great choice for Jersey farmers because of its drought tolerance, pollinator-attracting blooms, and lack of palatability to the herds of deer that plague area gardeners and farmers.

Some customers are surprised to hear the seeds are from Elmer, Kieffer says. “A lot of people around here think that that’s really great, to have [a source] that’s real local, and that’s what attracts me as well.” Kieffer has also included EFN seeds in crop planning for the small CSA program he runs on his property. His members can expect to see Dietrich’s raab, as well as the Homs eggplant and some of the EFN’s rare tomato varieties, in their shares this season.

“Those guys, they’ve got some wild stuff,” Kieffer says. “I’m not putting sorghum and things like that in the CSA boxes.” Kieffer focuses on EFN crops that have a history in South Jersey, like the tomatoes, eggplant and raab, even if the varietals are new to the area.

An avid beekeeper and good neighbor, he helped to install bee boxes at EFN’s home farm this spring. For the next several years, Kleinman and Hinz will concentrate on building their network. In 2016, EFN distributed seeds to around 200 growers around the world; they hope to collaborate with thousands of members in five years’ time—and for the network to take on a life of its own, rather than depending on the duo’s outreach and relationships to expand. “We want the website to be the hub for connecting people to these projects,” Kleinman says. “We want to expand that and get people doing the most exciting, pathbreaking research using our site.”

Kleinman and Hinz are focused on refining their operation and improving their website to be an even more functional tool. “We’re building a network, we’re growing on this three acres, we’re starting to sell seeds, we’re doing a whole bunch of different stuff,” Hinz says. “The biggest challenge has been piecing it together with two people.”

They receive support from their board, which includes seed-saving luminary William Woys Weaver, but it’s the two of them on the ground, literally, every day during the growing season.

For all of us struggling to cope in a time of climate change, the Experimental Farm Network provides not just a political stance or scientific theory on an issue that’s affecting our present and putting our future into question. They provide the opportunity for farmers and gardeners to create progress through collective action to reduce elevated carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. You can support the Experimental Farm Network by becoming a networked grower or contribute much-needed funds to their cause if you’re ready to roll up your sleeves and get your hands dirty to save the planet.

I left the farm with a parting gift from Hinz and Kleinman—Purple Koronis bush beans from Sudan, plus two varieties of sorghum, Coral and Kassaby, to plant in my West Philadelphia community garden plot, along with an instruction sheet on their sorghum project. I’ll be attempting to cross the two varieties according to their instructions, then reporting back to EFN headquarters with information and some of the resulting seeds—those that don’t get cooked green or dried and saved for my pantry. Maybe I’ll even make a teeny-tiny batch of molasses with the canes.

The Experimental Farm Network

experimentalfarmnetwork.org

nathankleinman@gmail

Triple Oaks Nursery & Herb Garden

2351 S. Delsea Drive, Franklinville, NJ

856.694.4272

tripleoaks.com