Legacy Lost (And Found)

How one cookbook author honors her grandmothers with the recipes they never taught her

I didn’t learn to ferment vegetables at my grandma’s knee, and I didn’t learn it from my parents. In fact, my parents don’t know how to ferment vegetables and they have little desire to eat them. So for the past several years of my obsessive fermentation habit, I assumed I was the funk-loving black sheep of the family and that my new vocation was unrelated to my roots.

I knew that every culture on Earth has some tradition of food fermentation. I knew, too, that the countries of my ancestors (France, Ukraine, Poland and Germany) have long been noted for their delightful ferments (wine, cheese, bread, beer, pickles and sauerkraut, to name just a few). Still, it wasn’t until I started writing my book that I learned how recently fermentation had played a role in my own family’s cuisine.

I live near the Italian Market, where I can easily find the ingredients needed to make kimchi or to nixtamalize corn. To find Eastern European fermentation inspiration, though, I had to travel up to Bell’s and NetCost Market in the Northeast. It was at the unimaginatively named NetCost that I found the culinary stimulation I was looking for and much more.

From the moment I walked through the door, I was hypnotized by the enormous pickle bar, with its dozen varieties of cucumber and beet pickles, many fermented, as well as less familiar candidates for pickling, including fish heads and iceberg lettuce, bobbing in brine. I spotted blintzes, stuffed with sweet farmer cheese and cherries, while snippets of Polish and Ukrainian conversations serenaded me. I inhaled deeply at the 20-foot-long deli counter devoted almost solely to smoked fish. I understood the need for 17 kinds of feta cheese and 11 brands of milk kefir. I saw the pickle aisle, towering with every imaginable variety of pickled vegetable, and I didn’t find it redundant just because it was three feet away from the aforementioned pickle bar. It all felt right to me, just the way fermented vegetables have always tasted right to me.

I had a revelation while I stood among those pickles in that Eastern European supermarket. No, I hadn’t learned fermentation from my mother and she hadn’t learned it from hers. But I suddenly had no doubt that both of my grandmothers had learned it from their mothers (this was later confirmed by aunts and great-aunts) and that for many generations before that, a fermenting tradition had been passed down from mother to daughter.

For whatever reason, my grandmothers had been the ends of those very long lines. Maybe it was their daughters’ educations and opportunities that had made the act of slow, thoughtful food preparation seem antifeminist. Maybe bacteriophobia had begun sweeping the nation when my parents and their siblings were young, making them erroneously believe that krauts and half-sours were gross or dangerous, in spite of their alluring, sour bite.

Or maybe it was something worse than that: Maybe these methods were associated with the Old World, and a prejudiced view of immigrants said these practices (and these people) were unclean. Maybe, just as my grandparents and great-grandparents neglected to teach their children the languages of their homelands, for fear that they would be found wanting as Americans, they neglected to teach them to make the more distinctive, fermented flavors of home.

Unfortunately, both of my grandmothers have passed, so I’ll never know for sure what their reasons were. But peering into the NetCost pickle vats, I felt deeply connected to those ladies through my fermentation habit. Although it had skipped a generation, I was bringing these pungent, healthful and invariably slow foods back to their humble, yet unforgettable, place on the table.

These realizations continue to inspire me to ferment, but more important, they inspire me to teach the making of these distinctively flavorful, bright foods that require vegetables, patience and not much else. This is why I teach fermentation classes—not just because there’s great interest in the health benefits and incredible flavors, but also because I feel a joyful obligation to play my role in tying our culinary past to our culinary future.

This is also why I make a special hot-pink beet kvass for my niece, Ava, and why I have her with me, chopping vegetables and measuring seasonings, when I make it. It may not be her favorite beverage yet, but I hope that one day, those fermentation-friendly genes will kick in, and she’ll become part of the long and nearly unbroken line of kvass-making Feifer women.

Editor’s Note:

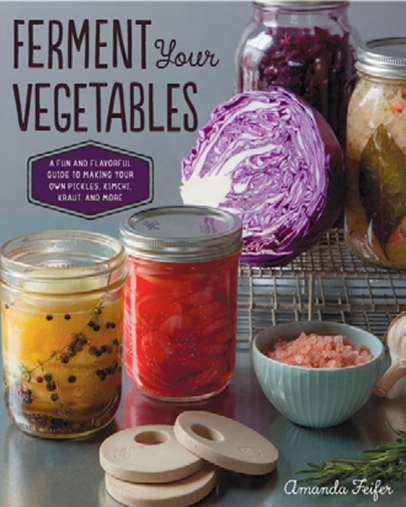

Amanda Feifer’s book Ferment Your Vegetables will be published by Fair Winds Press this October.