Pantry Power: The People's Kitchen

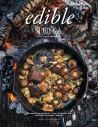

IT’S WEDNESDAY AT THE PEOPLE’S KITCHEN, and April McGreger is making lunch. Standing over a low burner in the shared kitchen space on South 9th Street, the chef, master preserver, and writer stirs an enormous pot of potatoes, sweet potatoes, peppers, and onions with a long wooden paddle.

Behind her on a stainless-steel countertop is a tub of aromatic ham hocks and neck bones, long-simmered for stock, waiting to be picked of their savory pink meat. On another, packs of frozen pork sausages—pulled from grocery cases just shy of their sell-by date—thaw before they go into the pot. The ingredients were donated to the nonprofit kitchen—a collective of chefs, students, and neighbors who prepare and distribute free meals—from area supermarkets and food rescue organizations.

“I don’t even know what’s there until I get here that day,” McGreger says. “One of my very favorite parts about this work is the creativity, having to think on your feet and piece together all these different things to make it all work.”

The improvised stew will be packaged and distributed with a side of rice outside the kitchen’s Italian Market storefront that afternoon. But today’s lunch will get flavor, color, and character, not to mention a nutritional boost, from a batch of vivid, fiery kimchi McGreger prepared nearly two years ago.

That kimchi is just one of the dozens of preserves—pickles, vinegars, jams, syrups, sauces, pastes—that McGreger has put up in The People’s Kitchen’s pantry. She’s worked for the past few years as a paid employee or as a volunteer with the food-access nonprofit, which was founded by chef Aziza Young, former tenants El Compadre, and 215 People’s Alliance in response to the pandemic in 2020. With her guidance and expertise, donations ranging from overripe bananas to jugs of date syrup to fish bones have been transformed into nourishing ingredients that add distinctive flavor to the kitchen’s thrice-weekly meal distributions.

“I always say I’m a preservation practicalist. I will preserve anything that needs to be preserved in the best way that I think it can be preserved,” McGreger says. “The individual vegetables inspire me a ton, and I draw really hard often on my own culture, my own up-bringing: rural, Southern, agrarian culture stuff.”

“If we didn’t get any donations at all this week, we could still make something delicious. It’s a bit of a ‘stone soup’ mentality just by having a stocked pantry

McGreger grew up in a deep-rooted farming family in rural Mississippi—her brother still grows sweet potatoes there—and food was always a big part of their lives. She majored in geology, and grad school brought her to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where she connected with the local farming community and studied sustainable agriculture at the local community college. When her program’s funding dried up, she decided to pursue a career in food, starting with a job at the acclaimed Asian-Southern restaurant Lantern. Over more than five years in that kitchen, McGreger transitioned into pastry.

She began making jams, pickles, and other preserves out of bumper crops from friends’ farms. “It was just part of the culture,” she says. “It was valued and fun and a way to feel useful, bond, and eat well on the cheap.” McGreger founded Farmer’s Daughter, a preserves company that broke records with the many Good Food Awards it won over more than a decade in business. By 2018, McGreger was married with a son, years of working in kitchens were taking a toll on her body, and North Carolina’s hard-right political shift in 2016 had the family looking for a new home. She closed the business, and they moved to Mt. Airy to be closer to her husband’s family.

In her new city, McGreger volunteered with 215 People’s Alliance, which served as The People’s Kitchen’s fiscal sponsor early in the project, during the 2020 election. The next year, chef Valerie Erwin suggested that McGreger step into a leadership role and bring her knowledge of fermentation to the kitchen, which initially used donated food and funds to put laid-off chefs to work making free meals for community members.

“April has a really broad skill set, and fermentation is something that people really know her for,” says Erwin, who serves with McGreger on the organization’s executive committee. The two met at a conference nearly 15 years ago and bonded over their shared love of Southern food; since then, they’ve collaborated on cooking classes and farm dinners. “It’s the idea that, ‘This is food, this is edible, and I can make it into something delicious, and it requires some commitment and creativity,’” says Erwin. “She’s very good at making something out of what many of us would think of as nothing.”

Collaborating with other tenants in The People’s Kitchen feeds that creativity. Worker-owned masa company Masa Cooperativa rents the kitchen for its weekly production days; McGreger transformed their fresh-milled, locally grown masa into a Three Sisters–themed, sweet-savory miso along with heirloom beans and winter squash. When Fishadelphia’s community-supported fisheries project used the kitchen to filet their weekly catch, she made the discarded fish parts into the kitchen’s own bespoke fish sauce.

Under McGreger’s guidance, the contents of the reach-in fridge at The People’s Kitchen more closely resembles a Michelin-grade chef’s R&D shelf than a food pantry’s cupboard: Bright vinegars made from bananas, grapefruits, and dates. Jars of deeply colored pickled beets, salted col-lard greens, and green tomato tapenade. Jams made with juneberries, raspberries, and blueberries harvested from urban gardens and city trees. Earthy house-fermented black garlic and a Berbere-like paste of long-fermented heirloom peppers.

“It’s definitely flavor building, and with fermented vegetables, it’s also providing nutrient density,” she says.

When McGreger isn’t volunteering at The People’s Kitchen, consulting with restaurants, or teaching classes and creating educational materials for a local homeschooling collective, she writes about fermentation and preservation to educate home cooks. Her cookbook, Jam On! Everything You Need to Know About Canning & Preserving, was published in 2022. Paid subscribers to her email newsletter, Preserving the South, receive recipes, musings, and canning tips. Those on the highest-paid tier even receive an annual box of her homemade preserves—a way of managing the abundance of her home canning habit while giving longtime Farmer’s Daughter fans a way to taste their favorite products.

McGreger wants busy home cooks to know that fermentation projects can be manageable—they don’t have to be all-day affairs wrangling big crocks of kraut or baby-pool-sized batches of kimchi. She believes that just about every cook—and every kitchen—can find time and space to ferment.

“I think of fermenting vegetables as banking time,” she says. “You can get really fast at making a quart or pint of curtido or sauerkraut or kimchi or fermented carrots—really small-batch, fermented vegetables with a sea salt brine and whatever spices you want to add. That can stay in your fridge for literally a year without going bad.”

Fermenting vegetables also makes their nutrients more bioavailable, whereas fresh produce gradually loses nutritional value as it sits in your crisper before it eventually spoils. The beneficial microbes responsible for fermentation stave off spoilage and potential pathogens by outcompeting bad bacteria that may be present in your jar of pickles or crock of kraut.

Those benefits come in handy for McGreger as she looks for ways to incorporate vegetables into menus at The People’s Kitchen. “Salads are a little bit tricky,” she says, referencing the relatively high food safety risk of leafy greens like lettuce and spinach, which is especially important to keep in mind when vetting donations. “You’re increasing nutrient density, and you’re also improving food safety, which I think is a pretty cool thing about fermentation.”