The Butcher & The Chef

cow etching by raven; chicken etching by elenkoss; pig etching by doublebubble_rus - all stock.adobe.com

How one good food entrepreneur is making it easier for restaurants to source local meat

You’re probably accustomed to eating local heirloom tomatoes, salad greens and sweet corn at your favorite independent restaurant. In 2018, the farm-to-table movement isn’t exactly a trend, but it’s left a lasting mark on New American food, with the best chefs in our region going straight to the source and paying a little extra for ingredients that are produced using regenerative agricultural methods. They don’t do it because it’s cool (although to a locavore like me, it definitely is). They do it because it tastes better, and because it’s the right thing to do.

Of course, getting fresh, locally produced, sustainably grown food into restaurants isn’t always that simple. Sourcing with that level of integrity at a tiny, chef-driven BYO or an innovative, well-resourced fine dining spot may be easier to pull off, since diners expect to pay a premium. But what about a casual setting like a brewpub or a family restaurant? In that price-sensitive situation, it’s tough to buy local tomatoes for the burgers, let alone expensive grassfed beef from a local farm.

But at least one restaurant in the Philly area has cracked the code to serving delicious, sustainably sourced and affordable meat— thanks to a partnership with a new kind of butcher.

A bartender fills growlers at the Tired Hands Fermentaria in Ardmore.

A bartender fills growlers at the Tired Hands Fermentaria in Ardmore.

Starting Small, Growing Big

When Jean Broillet IV opened the Tired Hands Brew Café in 2011, the menu was small, like the space itself, but the food set a high bar. Bread for paninis was made in house, as were lacto-fermented pickles. Cheese and charcuterie came from producers within 100 miles of the tiny Ardmore restaurant. Thoughtful sourcing for simple, fresh menu items made sense alongside Broillet’s carefully crafted, limited-edition brews.

Whether it’s scouring the neighborhood for cherries or ordering produce from small-scale farmers in Lancaster County, Broillet thinks that local ingredients just make sense for his seven- barrel brewery.

With its dank, hazy IPAs and trippy, DIY-style marketing, Tired Hands grew from neighborhood gem to nationally-recognized brewing destination. Broillet knew they’d need to go a little bigger to keep up with demand.

He and his team ended up going a lot bigger. Tired Hands Fermentaria opened in 2015, just a few blocks from the Brew Café, with the capacity to brew 10,000 barrels a year. But the Ferm, as the Tired Hands crew calls it, didn’t house just their production and distribution space: it also included an expansive, 200-seat restaurant with an industrial vibe and an open kitchen, plus a full-service menu of pub fare worthy to accompany Broillet’s beer.

But designing a menu that could be executed with a kitchen staff of four in a tiny space proved to be much easier than building a full-service menu without those limitations— especially if Tired Hands wanted to keep sourcing from local purveyors and making ingredients in-house.

Bill Braun started working for the company in 2012, making pickles and paninis at the Brew Café. “I could tell it was special even then,” says Braun, even though, before begging his roommate, who worked at Tired Hands, to get him a job, the most foodservice experience he had was working in the grocery department at Whole Foods. Now, he’s Tired Hands’ head chef.

The Fermentaria opened with unusual tacos, inventive veggie-heavy dishes and pub classics like fried chicken—none of it locally sourced, except for the San Roman tortillas ordered in from South Philly. “We threw local out the window in order to just get the Fermentaria open, get it running and get an idea of what we were getting into,” says Braun.“That started to feel uncomfortable and unnatural after a while.”

Braun and Broillet both wanted to bring the Ferm’s food menu into alignment with Tired Hands’ reputation and the team’s belief in local, thoughtfully produced goods.

“I was trying to figure out where it would be impactful, and where it would be possible, in a place that large,” Braun says. “Meat was something I kept coming back to.”

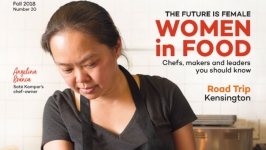

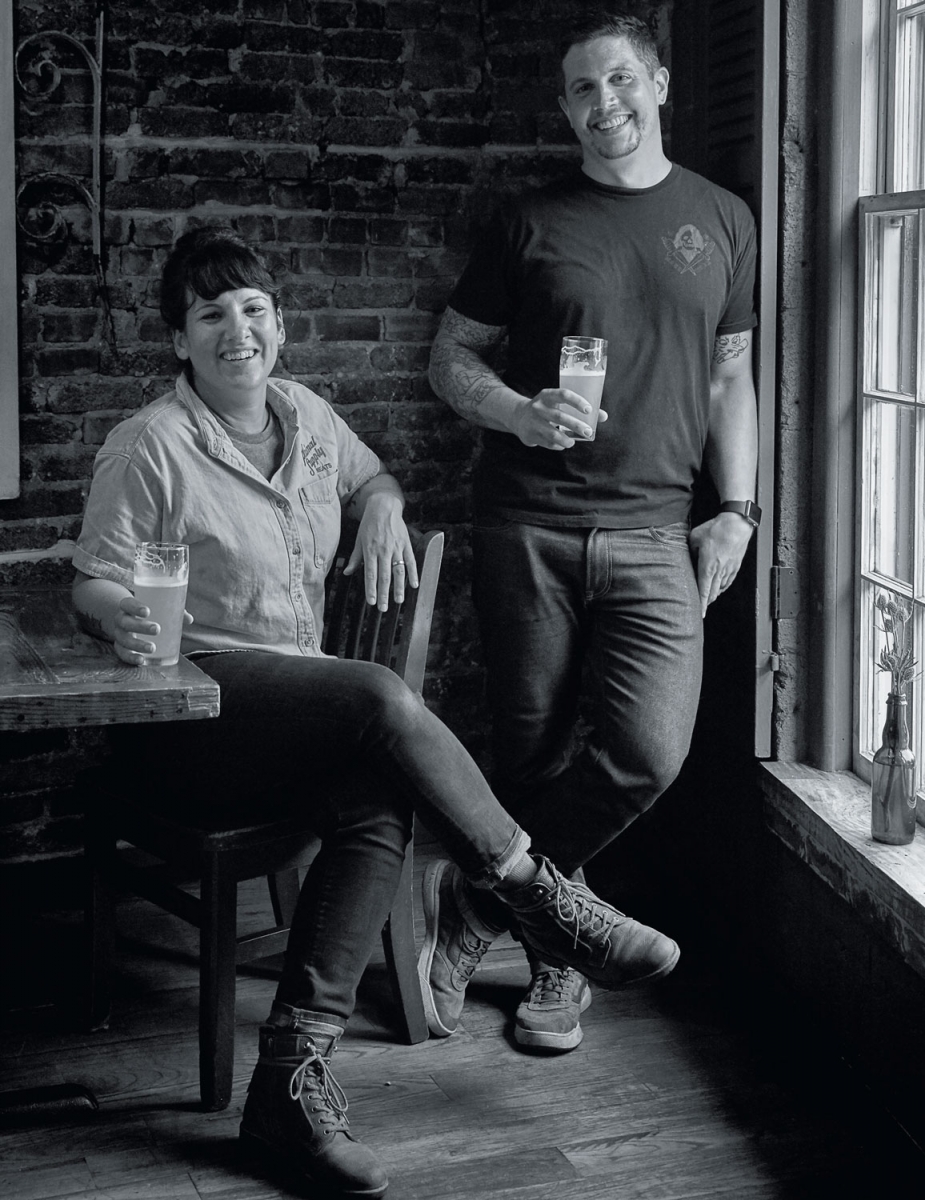

The Butcher Heather Thomason is on a mission to bring better meat to everyone.

The Butcher Heather Thomason is on a mission to bring better meat to everyone.

The Chef Bill Braun believes it's worth the effort to get local meat on the menu.

“All the chefs that we work with, they have to want it. The person who’s not truly driven to do local and commit to that sourcing, to have that extra conversation about which cut works—it’s not gonna work for them.”

Local Meat on the Menu

Even before she started Primal Supply Meats in 2016, Heather Thomason could see that Pennsylvania livestock farmers could use some help getting their meat to customers. As head butcher for Kensington Quarters, which began as an ambitious, whole-animal butcher shop-slash-restaurant, she was used to constant communication with farmers and meat processors about quantities, logistics and product quality. But she knew that for most chefs, restaurants and farmers, getting great meat from pasture to plate was a big challenge.

Braun first tried to localize Tired Hands’ meat supply on his own, sourcing pigs from Ironstone Farm in Pottstown and arranging for Thomason to teach a whole-animal butchery class for the Ferm’s kitchen crew. But after buying three or four animals and running into logistical challenges in the kitchen and then a temporary drop in supply from the farm, Braun knew he couldn’t manage the farm relationship directly.

At the same time, Thomason was preparing to leave Kensington Quarters and test out a middle-of-the-chain business model: she and co-founder Cecilie May would manage the sourcing, processing and transportation logistics of pasture- raised local meat for farmers, chefs and consumers. She’d buy whole animals from farmers, then process and sell primals and high-value cuts like loin steaks to luxury restaurants.

She’d balance the supply by selling other cuts at farmers’ markets and through a CSA-style Butcher’s Club subscription for consumers with neighborhood pickup points all over Philadelphia.

Not long after she started Primal Supply, Thomason and Braun reconnected. They collaborated with Broillet on one of Tired Hands’ Organoleptic Cartography dinners, deep dives into tasting and pairing ingredients with the brewery’s beers.

The butcher and the chef got to talking, and by the end of winter 2017, Primal Supply was sourcing, butchering and delivering one tender, whey-fed Ironstone pig—that’s 250 pounds of pork—per week to the Fermentaria. Since Braun was taking the whole pig, head and all, Thomason didn’t have to find a home for undesirable cuts, and Braun didn’t have to spend time coordinating with the farmer and processor or breaking the animals down into large-scale primals himself.

“It was a really symbiotic thing from the beginning,” Thomason says. “We didn’t have to worry about what we would do with the heads or other parts of the pig, because Bill was taking the whole thing.”

The Fermentaria’s pub-esque yet freeform menu was a perfect fit for this arrangement. Much of the meat could be braised low and slow for carnitas or pulled pork sandwiches. Pork belly could be highlighted in bao buns. Odds and ends like feet, head and skin would be turned into stuffed trotters, head cheese or chicharrones.

And rather than trying to put a finite number of pork chops on the regular menu, Braun initially sold them as specials. (At this point, Thomason simply swaps the loins out for additional shoulder meat from another pig, which Braun can use more readily for his staple offerings.)

Next came beef—literally a whole different animal. There was no way Braun could go through an entire 1,000-pound beef every week, but he and Thomason were able to provide balance for each other here, too.

Since she’s got an outlet for loin and mid-range steaks, Thomason simply brings Tired Hands around two animals’ worth of trim—the bits and pieces of fat and meat, accumulated during the butchering process, that make up ground beef for burgers—plus big braising cuts like shoulder and round to use for barbacoa and roast beef destined for the Brew Café’s sandwiches.

“Their volume let me increase my commitments to farmers from two to three animals, and then to four animals per week, because we have this guaranteed market for it at Tired Hands,” Thomason says. With the Primal Supply butcher shop on East Passyunk Avenue open and the Butcher’s Club and restaurant sales growing, she’s now sourcing five or six beef per week from her partner farmers—and she was able to scale up in the first place thanks to the Fermentaria’s demand for tacos and burgers.

Braun has seen a change in his kitchen staff, too.

“When we made the first delivery, Bill sent me a text saying, ‘I never thought I’d see my line cooks flipping burgers with such reverence,” Thomason says. “Their staff is very proud of the food. They have more of a relationship with it.”

Progress, Not Perfection

With pork and beef taken care of, Braun and Thomason had worked out a pretty seamless system. But six months in, Tired Hands was still using conventional birds for its fried chicken entree and chicken tacos.

Thomason sources pasture-raised broiler chickens and eggs from Gobbler’s Ridge Farm, run by Katie and Henry Esch, an Amish couple in Lancaster County.

“It took three or four months of talking and thinking about it to figure out how to make it work,” Braun says. He also made a visit to the farm, where he was able to see how Henry cared for his flocks, and even committed to sourcing Gobbler’s Ridge duck through Primal Supply.

“We had to earn his trust,” Thomason says. “Farmers often get burned with commitments—chefs say they want to do something, and then it doesn’t work out, and animals are on the ground and they don’t buy them. [Esch and Braun] needed to meet in person and mutually understand the value.”

Still, Braun wasn’t sure he could make the price of the chickens work—but all he had to do was think outside the bird a little bit. “What clicked was that we could butterfly the breast, so we’d get four for chicken sandwiches, plus two fried chicken entrees out of the bird,” he explains. “That was just enough for the math to make sense.”

Once Braun solved the problem of how to put a high-cost, high-input item like pastured chicken on the menu, Thomason was able to double her orders from Gobbler’s Ridge. Now, his whole staff knows how to butcher a whole chicken, and she’s sourcing 150 birds from the farm each week.

While the wings are still conventional—”there could never be enough,” Braun says—and bacon is sourced from Yeadon-based 1732 Meats, the duo are proud of what they’ve been able to build together for Thomason’s farmers and Braun’s customers. They’re still thinking about what’s next—like rabbit rillettes, chicken liver pâté and house-cured ham for the Brew Café, and seeing if there’s a way to get a steak on the regular menu.

Thomason is eager for other mid-priced restaurants to see the Fermentaria’s success and push to source better product for their own kitchens.

“All the chefs that we work with, they have to want it. That’s part of my model, and that’s okay. The person who’s not truly driven to do local and care and commit to that sourcing, to have that extra conversation about which cut works—it’s not gonna work for them . . . but once it’s on, we take care of people,” says Thomason.

Braun is clearly one of those chefs who’s willing to put in the work. “For me, it was more about, how do I make sure that [what we’re serving] is something I’m 100% comfortable with and falls under the umbrella of our values,” he says. “That was the motivation more than anything else. I’ll figure the rest of it out as long as I can do that.”

Thomason also sees the Primal Supply– Tired Hands partnership as a replicable model for other chefs, partially because the benefit extended all the way back to the start of the supply chain.

“I’m really proud of this, and I think other people can do it,” she says. “It helped our business grow; it helped me support more farmers. . . . I want more people to know about it so they’re motivated to try to do it, too. It’s achievable.”

Pig Problems

Pigs raised on factory farms contribute to pollution. Waste from industrial ag has polluted 35,000 miles of river in 22 states across the country.

Better Beef

Meat from pastured cows has less total fat as well as more omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants compared to conventionally raised cows.

Soup's On

Whole chickens help chefs and home cooks reduce waste. Backs, necks, and feet are all commonly discarded parts that make great chicken stock.

5 UNDERVALUED CUTS OF MEAT and how to make them delicious

Butcher Heather Thomason shares her tips for making the most of the whole-animal butcher counter with these lesser-known, more affordable cuts.

Ground Beef

It’s one of the cheapest types of meat you can buy. Just don’t get stuck in a burger rut. Thomason recommends using an 80/20 blend to make tacos, meatballs, and chili.

Coppa Steaks

This cut of pork is used for making capicola (aka “gabagool”), fresh cuts make a great steak. “We love the juicy fat and flavor of a coppa steak cooked in a cast iron skillet,” Thomason says.

Bavette

Bavette, also known as flap steak, is a great substitute for skirt steak. It’s thick, tender and tasty. “Seared and sliced across the grain, it’s one of our favorite cuts of beef.”

Beef Shanks

These are an inexpensive substitute for short ribs. By the time the beef is braised and tender, the marrow from the center bone will have melted, yielding a rich, beefy sauce.

Pig Heads

There are a lot of meaty, tasty bits to be had off of a head. With a whole head, you can make head cheese or pozole. Or slow-roast and serve a whole pig head for your next taco party.

from top: fried chicken, bbq brisket, carnitas tacos

from top: fried chicken, bbq brisket, carnitas tacos